About this Event

Program

1:30 PM | Gallery Opens

2:00 PM | Curator's Tour led by Students

2:45 PM | Break

3:15 PM | Panel I: Ending The Plantation-to-Pr*son Pipeline in the Mississippi Delta

4:15 PM | Break

4:30 PM | Panel II: Ending the Coalfield-to-Pr*son Pipeline in Appalachia

5:30 PM | Concluding Remarks

6:00 PM | Off-Campus Happy Hour (Co-Op at 33/Chestnut)

***

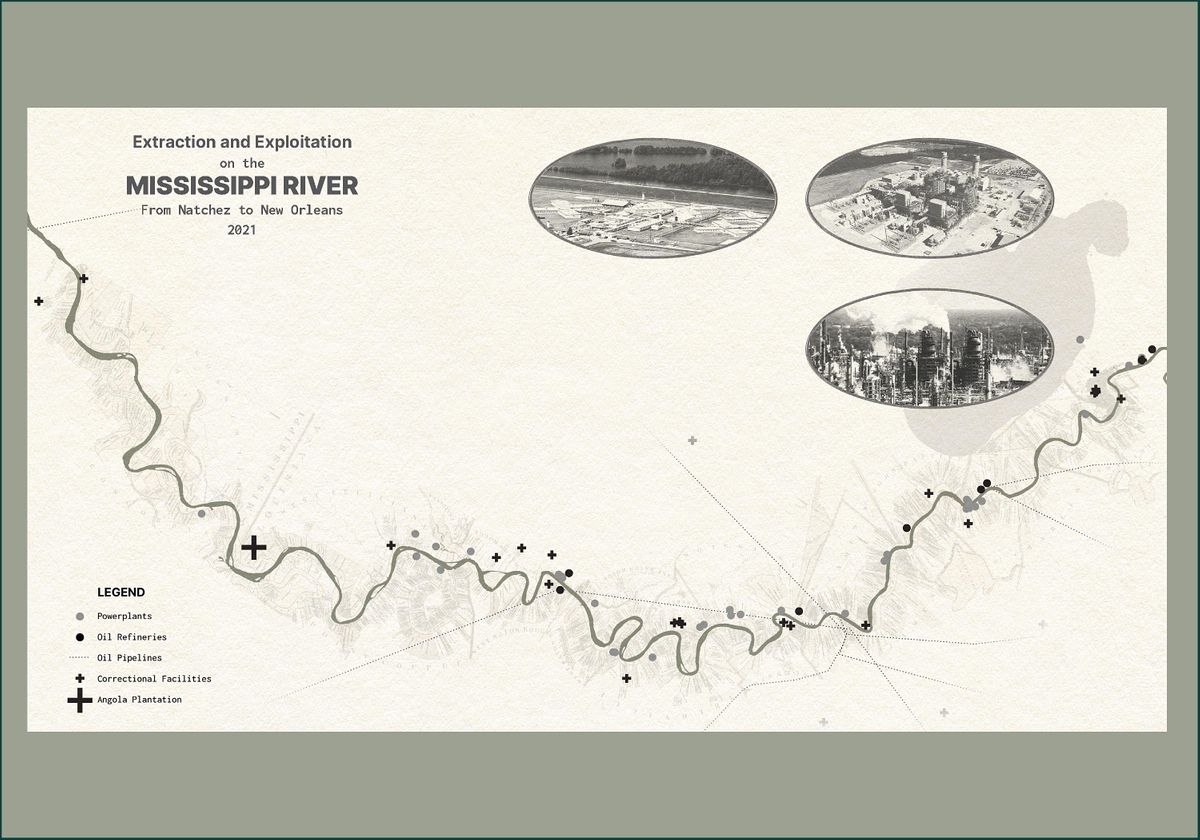

This studio is the third in a sequence of "Green New Deal" (GND) studios organized by the McHarg Center. In its first iteration, students were asked to identify priority zones for the first wave of public investment that a GND might make possible. Their work, which won an ASLA National Award of Excellence and served as the framework for the "Green New Deal Superstudio", focused on Appalachia, the Corn Belt, and the Mississippi Delta. In its second iteration, students were asked to work in those regions and focus in on three key industries in the fight for a GND: the carceral, fossil fuel, and industrial agriculture systems. In this iteration, students were asked to focus on those same industries in Appalachia and the Mississippi Delta through three key sites in each: USP Letcher, Big Sandy, and McCreary in Appalachia; Parchman, Angola, and Lafourche penitentiaries in the Delta. The exhibition will feature work on the political economic history and present of each region's built environment alongside a series of "climate fictions" illustrating the kind of worlds that would be possible in Appalachia and the Delta post-fossil fuels, prisons, and industrial agriculture.

Rather than a conventional final review with individual boards and a jury of design critics cloistered away with the work, this studio will present a public exhibition on the built environment agenda a Green New Deal could bring.

**

Americans are living through the early days of the climate crisis—through Hurricane Maria and its impact on the Puerto Rican diaspora, through Hurricanes Sandy and Harvey and the drowning of America’s coastal cities, through this spring’s record flooding in the Heartland and its devastating effects on farming communities and Indian Country, through the wildfires in Paradise and last year’s second Big Burn, and through this summer’s roiling heat that can no longer be viewed as a wave but as the beginning of our planet’s big, long sweat. Yet the conspiratorial neglect of climate change by Republicans and its trivialization by Democrats at the federal level has left the nation in a perpetual state of triage—trying earnestly, if hopelessly, to recover from these disasters with limited funds and authority while an endless queue of worsening floods, storms, droughts, and wildfires approach. The climate crisis is here and there is no plan to address it.

The absence of federal climate action has given some urbanists leeway to trumpet claims that cities and metropolitan regions are now leading on the issue. At its most basic level, this is true—without any real federal investment in climate change, cities and regions have had to become leaders, regardless of the insufficiency of the measures taken. It is easy to lead on climate when the bar for doing so is on the floor. Mayors simply must step over it.

Much of the work mayors and urbanists now point to as evidence of their ability to lead on climate can be traced back to the Rockefeller Foundation and its recent focus on resilience—first, its jointly administered “Rebuild by Design” (RBD) competition in New York after Sandy with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development that began in 2012, and then through the many derivatives modeled after RBD, including the recently canceled “100 Resilient Cities” (100RC) initiative aimed at accelerating investments in climate adaptation across the world’s most vulnerable communities. These programs focused on metropolitan regions and cities, addressing specific challenges to resiliency, overseen by city government. But leaving the challenge of climate adaptation in the hands of a massive private foundation and a handful of city officials—all of whom are constrained by short-term thinking and limits on the scale and scope of their action—has proven ineffective at best and disastrous at worst. Nearly a decade after Sandy, none of those local, resilience-focused projects have a clear path to implementation. All that most of the communities have to show for their efforts are a few glossy renderings—fictions of a world never built. It shouldn’t be surprising when technocrats like Andrew Yang proclaim that the only option left is to give each individual American a “Freedom Dividend” which they could use to adapt to the changing climate by moving inland or out of flood zones. Without strong, federal leadership, this—and planetary geoengineering—might become our best available option.

This is not to say that cities and mayors have no place in whatever national action that might be taken on climate. Quite the opposite, as any national-scale plan will require coordination by local officials in cooperation with municipalities across the country under federal oversight. But whatever action we take on climate, most people will not experience or comprehend the scale, scope, and pace of transformation by turning on a light powered by wind instead of coal or natural gas. Rather, they will experience it through the building energy retrofits that result in new, electric appliances and green roofs of public and market-rate housing. It will be recognized through massive investments in public transportation, including electrified Bus Rapid Transit systems and High Speed Rail between cities. It will be recognized through the cleanup of every single toxic or polluted parcel of land in this country, an effort that could form the backbone of a federal jobs guarantee that puts millions of people to work in communities long abandoned by the government. These, and many other major spatial propositions, are at the core of the Green New Deal.

On February 7th, 2019, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (NY-14) and Senator Ed Markey (MA) introduced H.R. 109, a non-binding resolution “Recognizing the duty of the Federal Government to create a Green New Deal.” In it, they provide a framework for a “10-year national mobilization” that calls on Congress to pass legislation that builds resiliency against climate change-related disasters, repairs and upgrades the infrastructure of the U.S. (including universal access to clean water), establishes a zero-emission energy standard, develops an energy-efficient and distributed ‘smart’ grid, upgrades every existing building to and requires that all new construction in the U.S. achieve maximum energy and water efficiency (among other standards), reinvigorates federal industrial policy to guide the growth of a ‘clean manufacturing’ sector, works collaboratively with farmers and ranchers to lower agriculture-driven GHG emissions, overhauls the U.S. transportation system through the development of inter- and intra-city public transit, invests in conservation lands and other ‘low-tech’ carbon sequestration solutions that also enhance biodiversity, remediates or repurposes hazardous waste and abandoned sites, and focuses on several other technology-driven emissions reducing investments.

In their press conference announcing the resolution, Ocasio-Cortez remarked that the public should view the Green New Deal legislation as a “Request for Proposals…we’ve defined the scope and where we want to go. Now, let’s assess where we are, how we get there, and collaborate on real projects.” Since then, a new body of policy development and economic research, headquartered at New Consensus, has emerged. But the work accomplished to date on the Green New Deal has been focused on abstract, national-scale economic and political strategies. None of it has dealt directly with the unprecedented scale, scope, and pace of landscape transformation that it implies.

In the two+ years since this announcement, several more concrete proposals have been developed concerning the implementation of the Green New Deal (nearly all of them connect to either this studio sequence or the McHarg Center). This includes work led by Daniel Aldana Cohen around public housing, Akira Drake Rodriguez around public schools, Johanna Bozuwa around public utilities, and Yonah Freemark around public transportation (forthcoming).

A national climate plan like the Green New Deal will be understood by most people through the buildings, landscapes, infrastructures, and public works agenda it inspires. Given the scope of these efforts, it’s clear that designers will play a central role in project managing the nation’s response to climate change both at the scale of the national plan and the built works through which Americans will experience this transition.

This studio will endeavor to give form and visual clarity to the scale, scope, and pace of transformation that the Green New Deal implies.

Event Venue & Nearby Stays

Meyerson Hall, 210 South 34th Street, Philadelphia, United States

USD 0.00